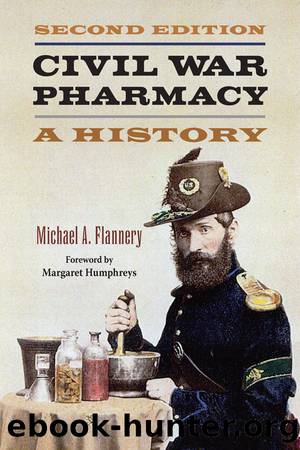

Civil War Pharmacy by Flannery Michael A.;Humphreys Margaret;

Author:Flannery, Michael A.;Humphreys, Margaret; [Flannery, Michael A.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Southern Illinois University Press

CHAPTER NINE

NAVAL PHARMACY

Comparatively speaking, only a small number of historians have paid attention to naval aspects of the Civil War and fewer still to the medical aspects on river and sea. The sheer lack of available secondary literature forces one to do considerable diving into primary sources to uncover the story. Nevertheless, such efforts are repaid by revealing the indefatigable efforts of men at all levels who attempted to provide adequate care to the sailors under their charge. What emerges is a story in which the production and distribution of medicines by the U.S. Navy forms an interesting if less studied aspect of pharmacy during the Civil War.

Medicine and medical care were decentralized components of the U.S. Navy until 1842 when the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (BUMED) was established, but with more centralized control came better coordination of function; by 1854, for example, with a more standardized âTable of Allowancesâ for medicines and medical supplies in place, medical supply was no longer slave to the individual preferences of shipboard surgeons. When war broke out in 1861, medical care in the U.S. Navy was provided by three categories of physicians: assistant surgeons (on average six years in grade), passed assistant surgeons (fourteen years of service), and surgeons (on average twenty-seven years of service).1 William Whelan was the chief of BUMED. At its height the Union navy had a total of 463 medical officers in 1864, a number that would fall off to 425 the following year.2

The Confederate States Navy Department offers an arresting contrast. For example, from October 1863 to October 1864, all five naval hospitals at Richmond, Charleston, Wilmington, Savannah, and Mobile admitted just under two thousand patients combined. The army hospital at Chimborazo, Virginia, alone admitted more than three thousand patients in just six months during the same period.3 Interestingly enough, in 1863, the so-called high-water mark of the Confederacy, William A. W. Spotswood, chief of the Confederacyâs Office of Medicine and Surgery, the Southâs counterpart to Whelan and BUMED, was able to report twenty-three surgeons on active duty, although he recommended the number be raised to thirty. While there were fifteen passed assistant surgeons, Spotswood noted that only eleven had been appointed and one of these died, so the effective number was reduced to ten. Given the current size of the Confederate navy, Spotswood thought that the anticipated ninety-three medical officers âof all gradesâ would be âsufficient for all the purposes of our present Naval Establishment,â but not if it were even moderately increased in size.4

Spotswood had little to worry about. One perceptive naval historian has noted that by training and inclination, Jefferson Davisâs âstrategic thoughts were strictly continental and landlocked.â5 As such the Confederate navyâs highest enlistments barely reached forty-five hundred and more normally was likely under three thousand men, the equivalent of less than three regiments.6 The entire Confederate fleet comprised only 113 commissioned vessels along with 3 torpedo boats, the Hornet, Scorpion, and Wasp.7 By comparison the creaky 90-ship Union navy of 1861 quickly

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| United States | Abolition |

| Campaigns & Battlefields | Confederacy |

| Naval Operations | Regimental Histories |

| Women |

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote(2702)

Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson(2459)

All the President's Men by Carl Bernstein & Bob Woodward(1971)

Lonely Planet New York City by Lonely Planet(1857)

The Murder of Marilyn Monroe by Jay Margolis(1751)

The Room Where It Happened by John Bolton;(1729)

The Poisoner's Handbook by Deborah Blum(1671)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(1632)

Lincoln by David Herbert Donald(1622)

The Innovators by Walter Isaacson(1612)

A Colony in a Nation by Chris Hayes(1530)

The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution by Walter Isaacson(1519)

Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith by Jon Krakauer(1425)

The Unsettlers by Mark Sundeen(1347)

Amelia Earhart by Doris L. Rich(1345)

Birdmen by Lawrence Goldstone(1345)

Decision Points by George W. Bush(1261)

Dirt by Bill Buford(1247)

Zeitoun by Dave Eggers(1231)